Safety Guidelines and Practices

The following are key safety considerations for conducting Street Medicine63:

- Situational awareness and safety precautions in a range of settings.

- An understanding of risk factors for violence.

- The use of clinical skills to prevent and de-escalate crises.

- Staff well-being including self-care and burnout prevention.

- Safety precautions for transporting individuals.

- Infection and infestation prevention.

- Preservation of institutional knowledge/memory.

- Assess history of violence upon intake. Take note of important information that partner agencies may know about a patient’s past behavior.

- Consider a person’s potential for violence based upon observed behaviors; for example, agitation, anger and impulsivity.

- Conduct an assessment for each patient with the information at hand to determine a patient’s current level of risk.

- Devise a plan of action with partners and supervisors that may need to be carried out when danger exists. This plan should include how and when to call security and/or police, and when to leave.

- Inform your supervisor and security personnel when you experience threats to safety and unusual developments in the field.

The team carefully navigates an encampment. Taken by Andrea Murray of St. Joseph Center.

b) Awareness of Environment and Physical Surroundings. Upon approach, conduct a safety risk assessment for each situation and site. Outreach involves inherent risks and team members need to take precautions against risks that are likely. Every space and setting is different with its own characteristics for safety precautions. Examples of environments include streets, tents/tables, encampments, community fairs, clinics, co-located agencies, homes of housed patients, and shelters.

Situational awareness and scene safety are primary concerns in street medicine. As with BLS, if the scene is unsafe, clinicians will not be of service. The clinician takes the lead on assessing scene safety. Scan the surrounding environment for 360-degree surveillance and plan to do the following:

- Know the names of cross streets and nearby addresses in case you need to request emergency transport to the location.

- Avoid trespassing while doing outreach; for example, Department of Transportation property along freeways is off-limits without escort and emergency transport vehicles may be unable to reach you in the event of an emergency.

- Use code words known to all team members to indicate it’s time to exit a situation due to safety concerns. When any member of the team says the phrase, leave the scene.

- Watch for weapons in plain sight. Ask patients to safely put them away before approaching or consider not approaching at all.

- Look out for common hazardous items found on a person or in an encampment including scalpels, needles, broken glass, knives and other utensils.

- Avoid handling or touching patients’ personal possessions.

- Look for untethered dogs/pets. Proceed with caution, ask about and observe the animal’s temperament before approaching. If an animal cannot be properly restrained, do not engage.

- Watch for threatening bystanders. Avoid approaching the vicinity of suspected high-risk situations involving drug dealers, loan sharks, pimps, gang members, domestic partners, or individuals using drugs or possessing paraphernalia including sharp needles.

- When possible, operate in areas with multiple egress routes for the patient and all members of the team, if any party should feel uncomfortable in the interaction.

- Use caution and wear gloves around biohazard risks including cuts, lacerations, puncture wounds, bites, stings, unintentional poisoning, infections and exposure to bodily fluids.

- Be aware of severe weather conditions and risk of wildfires. Be cautious in hot dry weather, adhere to alerts about high winds, flooding, earthquakes, hurricanes, etc.

Tips for personal preparation include:

- Assign safety roles with two or more outreach partners; roles can be designated where one team member provides surveillance of the site while another attends to the patient.

- Use self-insight to recognize one’s own role, behavior and emotions.

- Pay attention to basic feelings and instincts. Be aware of your own fear, discomfort, uneasiness, stress and anxiety.

- Come emotionally prepared and bring your best self to each situation.

- Be ready to leave the scene quickly if you encounter high-risk behavior that makes you feel uncomfortable or unsafe.

- Recognize and assess the level of intoxication prior to approaching or engaging with someone exhibiting signs of being under the influence. Patients under the influence of stimulant drugs who are experiencing psychosis can become aggressive and violent.65

- Be aware of a person’s signs and symptoms of untreated mental illness.

- Recognize your own desire to help and your limits in situations that may be unsafe.

- Be cautious around bystanders whose behavior appears out of control.

- Increase safety through consistency and relationship building.

Maintain heightened awareness and attention in order to:

- Avoid potential triggers of patients.

- Avoid re-traumatization.

- Establish clear roles and boundaries through collaborative team decision-making, such as advance planning for “who does what, when and how.”

- Respect privacy, confidentiality and give mutual respect.

- Honor cultural differences and diversity, such as age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation.

More de-escalation tips68 :

- Respect personal space.

- Establish verbal contact prior to approaching too close to someone’s personal space

- Use a respectful tone.

- Avoid provocative language.

- Lower your voice and speak slowly if a person raises their voice.

- Do not tolerate abusive language or actions. If someone is verbally abusive, say that you will be able to help once they calm down.

- Try not to interrupt and apologize if you do.

- Be concise.

- Set clear limits.

- Listen, ask questions, restate to clarify and avoid misunderstandings.

- Identify wants and feelings.

- Acknowledge the importance of the concern and your interest in resolving the problem.

- Offer choices, optimism and hope.

- Redirect, reframe, avoid blaming and accusing.

- Agree or agree to disagree.

- Try to reach agreement about next steps and arrange follow-up at the end of the visit.

- Plan for a safe, easy exit for both yourself and the patient.

- Debrief.

Have a ready reply with standard language such as69:

- This is a professional relationship.

- I’m not comfortable with that type of language.

- I’m uncomfortable with that behavior.

f) Emergency Protocol Steps. The following are basic guidelines in emergency situations:

- If you have a contingency plan in place for worst-case scenarios or dangerous situations (as mentioned above), activate it now.

- If any member of the team feels unsafe, the entire team should withdraw. The team can agree upon a code word that when used indicates an exit is necessary to avoid conflict.

- Call 911 or direct someone to call. Be prepared to provide an address and a description of the situation/emergency.

- Exit as expediently as possible.

Do not separate from your team or partner unless you are in imminent danger.

- Inform your supervisor and security personnel of any threats to safety and unusual developments in the field.

g) Safety Precautions for Transporting Patients. The following are suggested safety precautions for transporting patients:

- Be aware of risks associated with patient transport such as unintended outcomes when a patient is moved from one location to another; for example, falls, psychiatric decompensation, loss of unattended belongings, etc.

- Two-person teams are strongly recommended (a driver and a staff partner) for transporting patients in agency vehicles.

- Use safe techniques to assist individuals in entering and exiting vehicles.

- Use plastic and vinyl seat covers in vehicles to avoid transmission of head lice, body lice, and scabies.

- Spray and wipe seats with a disinfectant before and after transporting (Lysol, alcohol wipes, or bleach products).

h) Infestation and Infection Control Measures

- As always, use Standard Precautions when working with patients.

- When soap and water is not available, cleanse hands with alcohol-based hand sanitizer (at least 60% alcohol content).

- Avoid head-to-head contact with patients to prevent transmission of head lice. Clinicians should secure their hair in the same manner as the clinical setting.

- Avoid transporting heavily body-lice infested clothing, jackets or bedding (consider discarding these items). If the patient cannot part with any items, they can be secured inside of a plastic bag until they can be laundered with hot water and dried on high heat.

- Clean medical supplies such as blood pressure cuff between patients with lysol, bleach, or other approved cleaning products used in the clinic. Wipe down the van with the same type of products in the event of patient transport.

i) Preservation of Institutional Knowledge/Memory for Safety. Institutional memory, as applied to street medicine, refers to how teams record and recall important details of patients’ behaviors towards staff. Related to quality patient care and safety, this knowledge is important to preserve by capturing critical patient information through documentation in the patient record. This documentation helps to improve future decision making and avoid problems related to safety and quality of care. For example, a patient with a history of threatening behavior can inform future decisions only if this is recorded in their medical record.

It is important to document patient safety risks because you might leave your position. If someone else takes over with no knowledge of what occurred, that knowledge is lost and others could be in danger as a result. Documentation in a historical record is essential.

Steps to document a patient safety risk include:

- Recording relevant information in the patient’s chart (electronic medical record); for example, documenting specific threatening behavior including situation details, date, time, place, witnesses, etc.

- Informing agency security personnel, your supervisor and partner clinician.

- Filling out agency-specific incident reports

- Taking on the duty of passing on critical information to new staff; for example, do not assume the team remembers an incident or has passed on all of the information.

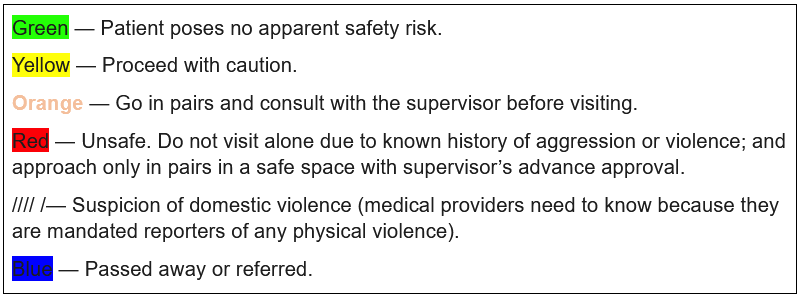

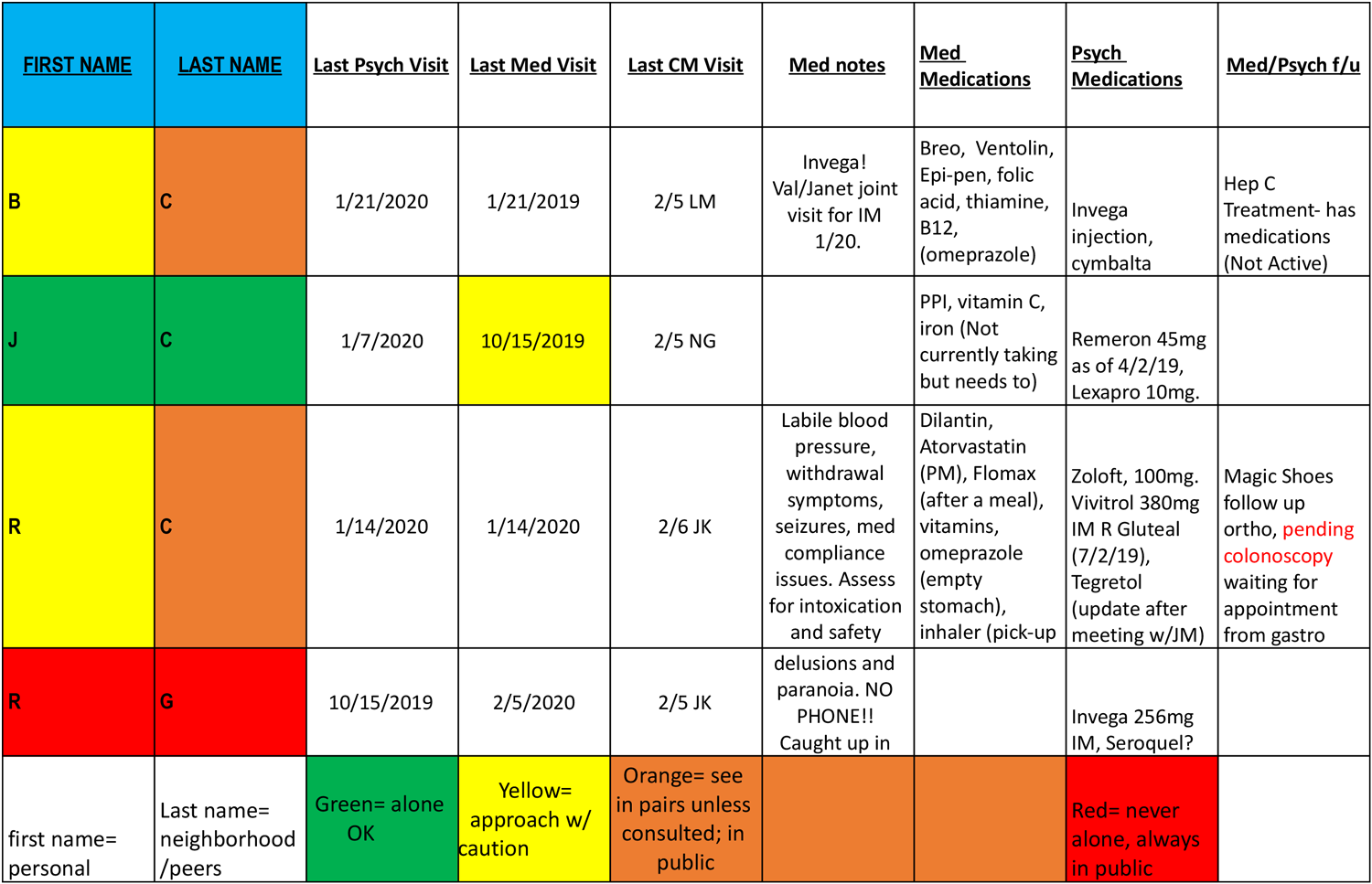

j) Flagging System Template for Safety Risk Documentation of Patients.

Venice Family Clinic, with partners St. Joseph Center and The People Concern, created an alert system to be used during case conferencing to identify and communicate risks of potential violence to clinicians. The flagging system uses the below legend assigning a color or symbol.

Street Medicine Flagging System. From Venice Family Clinic, St. Joseph Center, and The People Concern, 2014

The system can be used to remind the team about the safety concerns related to their patient’s risk for violence and the risk for violence related to the patient’s encampment, peers, or neighborhood. In the following example, the color in the column representing the patient’s first name represents the patient’s risk while the last name color represents the risk associated with the patient’s environment. Safety risk should be continually assessed and documented. Teams often conference on a weekly basis so they can review safety concerns prior to outreach.

What are medical clinicians mandated to report in the state of California?70

- Adults over the age of 18: report any visible injuries from assault or abuse inflicted by anyone (a stranger or someone known to the victim), including rape and sexual assault.

- Children under the age of 18: report any visible injuries from assault or abuse, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, rape and sexual assault, or any visible injury from or sign of neglect. Also report suspected assault, abuse, or neglect, regardless of the presence of physical signs.

- Report any visible injury inflicted by self or another when the injury was caused by a firearm.